Since its inception, Easel has used an open-source Javascript library called Fabric to handle drawing and interacting with projects on the 2D side. Fabric knows how to draw text and many kinds of shapes, how to select objects and move or rotate or resize them, and how to read SVG files created with programs like Illustrator and Inkscape. Using a preexisting library like Fabric let us build a functioning and useful product more quickly than we could have if we’d developed all that functionality from scratch.

Unfortunately, along with that head start came some awkward limitations.

Fabric was originally written for Printio, a site for custom-printing logos and artwork on t-shirts and other merchandise. Printio’s view of the world is very different from Easel’s: it has no need for concepts like 3D volumes, inner and outer profile cuts, or even physical dimensions.1 So Fabric omits these concepts, and offers no easy way to support precise positioning, snapping, line and curve editing, and other CAD-style features we’d like Easel to have.

Since Fabric is open-source, we can make—and have made—enhancements to it. But we’ve often found ourselves fighting Fabric’s abstractions rather than being able to embrace them.

A trip to an alternate dimension

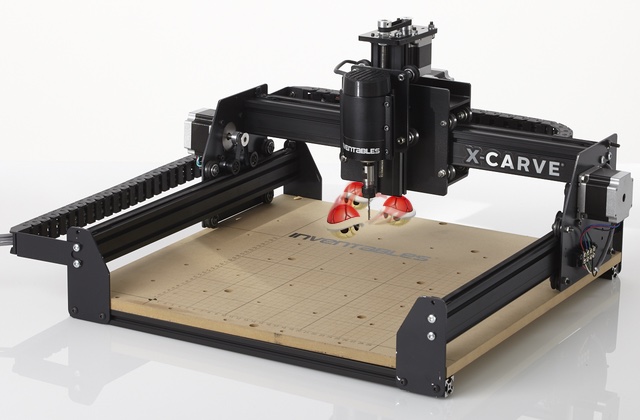

To understand what I mean about fighting abstractions, consider GRBL, the software that runs on the Arduino and controls the motors on your X-Carve. GRBL was designed for CNC machines, so it’s a great fit for running the X-Carve.

But suppose GRBL didn’t exist, and that the only pre-existing controller software was the AI that drives the computer opponents in Mario Kart. Mario Kart physics resemble real-world physics, but they are not identical. A Mario Kart AI wouldn’t natively understand stepper motors or 3-axis movement. And it would have logic dealing with a bunch of stuff, like banana peels and shells, that we didn’t really need or want.

We might be able to bridge the gap between 3D carving and Mario Kart, but we’d likely struggle to make it solid. Is there a CNC equivalent to the blue sparks that let your kart make sharp turns without losing speed? If a Mario Kart AI sees that it’s coming up behind Yoshi, instead of changing lanes to go around him, it might decide to use a lightning bolt to shrink him and then run him over. But that isn’t a good plan if, in shoehorning 3D carving concepts into Mario Kart, Yoshi was how we decided to represent clamps.

These shells will keep the bit from breaking…

Today we made the first step in migrating Easel to a new set of internal abstractions that are sturdier and more consistent than the ones we’d been letting Fabric impose on us. Easel projects now use a data model that better fits Easel’s purpose as a tool for designing and making real things. Everything is a three-dimensional volume measured in physical units. And the project data flows through the application in a consistent manner.

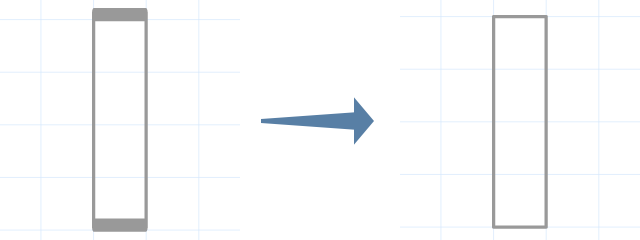

You may not notice anything different when using Easel. If anything, you should find that shapes feel more solid than before: they don’t slide around when you resize them, their outlines aren’t stretched, their cut depths don’t change when you reload your project or change your material.

We’re still using Fabric (for now) to render the 2D editor, but we have it in a much more deferential position. It’s no longer the primary source of your project data. When you click, drag, or type in the 2D editor, Fabric generates an event—but doesn’t directly act on it. Instead, your project is updated by code that’s written for Easel and aware of Easel’s 3D carving context. Information about the change flows downstream to Easel’s various panels and controls, and also down to Fabric. When something changes, the Fabric canvas gets the updated design spoon-fed to it.

This provides a clear separation between the data and its display and should help us make faster improvements in either area.

Stay tuned for a more detailed technical overview of Easel’s new architecture and a discussion of some of the things we’ve learned in adopting it.